Growing Up Buildings and 3 Principles for the Future of the Built Environment

A Personal Reflection on the Intersection of Architecture, Technology, and Human Experience and Guiding Tenets for Emerging Trends in Spatial Computing

“Rather than the bracketing characteristic of phenomenology, or the denial of experience found in structuralism, Lefebvre wished to see how the structures, signs and codes of the everyday integrate with biographical life…In recent years there has been a noticeable shift from questions of temporality to those of spatiality. As Frederic Jameson asks, “why should landscape be any less dramatic than the event?” In his work, Lefebvre suggested that just as everyday life has been colonized by capitalism, so too has its location — social space. There is therefore work to be done on understanding space and how it is socially constructed and used. This is especially necessary given the increased importance of space in the modern age.”

My very first memory is spatial.

I am two and a half and pressing my hands up against a floor-to-ceiling curtain window. Through the glass I can see straight across San Francisco’s Sunset district, over Golden Gate Park, all the way to the Richmond. The outside light is dimming quickly as the winter sun sets to the West highlighting the twinkle of the streetlights dotting the horizon.

This is always how the memory starts, me, hands up against the glass, the view ahead. And that’s the only part of the memory that is cinematic. The rest of the memory is spatial; planar even, like architectural sectionals.

There is the plane of the window in front of me.

The plane of the chairs directly in front of the window.

The plane of the waiting area behind me; and beyond that.

The plane of an array of columns delineating the circulation space for the elevator.

There is also the plane of a hallway somewhere to my left.

Navigating this memory is like using a joystick to pan the camera in a video game where the feeling that panning to view any given plane evokes is what is most notable.

Looking out the window feels safe and generous, the uninterrupted view is all mine to admire and absorb undisturbed.

Panning directly next to me, my mother; I cannot see her, rather I know it is her by a particular sensation of comfort.

Panning deeper into the waiting area, I feel the presence of others, and an awareness that I am not, in fact, in my own little world.

It is at this plane that I become aware that the interior lighting gives off a muddy industrial orange glow and that there are more planes further still from my perch like the circulation space.

I start to feel a worrying agitated bustle of new emergency room visitors entering behind me by the elevators.

My worry grows as I pan, finally, to the hallway which starts behind me and to my left, I feel the medical staff in there and what I suppose must be a sense of dread about my impending visit with the emergency room doctor.

And that is it, that is the memory: architectural and sensory.

This early memory reflects Lefebvre’s notion that space is not merely a backdrop to events but is integral to the human experience. Just as Lefebvre examined how everyday life is intertwined with its spatial context, my memory is an interplay of spatial and sensory experiences.

The spatio-sensory world.

(I feel as if )I have always navigated the world through the lenses of the architectural and the sensory. I have also gotten the distinct sense that not everyone else does. Thus, I have reasoned that, perhaps, I have some “innate” sensitivity that predisposes, nay, obliges me to see the world predominantly through these lenses.

To this end, I have collected two leading explanations for how this sensitivity emerged:

First, a proposal that this sensitivity is both literal and literally innate, my nature, if you will.

Perhaps my sensitivity is, in fact, a sort of socio-spatial synesthesia that crosses the senses of perception-of-affect with perception-of-real-Euclidean-geometry. As a temporal synesthete already, I am no stranger to conventionally separate senses being intimately and inseparably attached. In my case, time is inextricably connected to my visual field and perception of space. And this might be the sensitivity itself as research indicates that temporal synaesthetes are more accurate in their perception of Euclidean geometry than the general population.

On the other hand, it might have everything to do with how I was raised, the way I was nurtured.

My mother was a psychologist with an uncanny capacity of labeling people’s affect and from the age of 5-11 we remodeled our home ensuring that I was consistently surrounded by floor plans and trips to the San Francisco’s Department of Building Inspection’s Permit Services Office. It doesn’t get more concrete than that: I was seeped in buildings and behavior for the entirety of my youth.

If I were someone else, whether I have a biological or cultural predisposition to space and affect might have remained a casual and fleeting inquiry.

The unique thing about humans, they have unique interests. In this case, an interest in the relationship between space and affect could simply be:

a unique special interest, “did you know ‘drunk-tank’ pink-walls lead to agitation long-term?”;

a conversation-starting party trick, “when you enter a hotel room, do you choose the side of the bed nearest or farthest from the door?”;

a particular affinity for spaces that tickled a specific sensory experience in myself like the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg which kept me oscillating between feelings of bright awe and directional squishing.

Instead, and for whatever reason, for the last two decades my singular intellectual obsession has been understanding the science of the built environment’s effect on human experience.

Regardless (some things have no origin, or its origin is irrelevant, the phenomenon is present), I have cared voraciously about the built world since I can remember, and about finding literature to supplement this curiosity since my time as a high school in the mid-late 2000s.

During this these years, any bookstore I passed required a quick skim for any books that might answer my question: how do buildings affect us?

My routine thumbing through the social science, the psychology, and finally the architecture books always left me empty-handed, or with cousin-concepts:

The Situationist City by Simon Sadler (Sadler, 1998)

Design of Everyday Things by Don Norman (Norman, 1998)

These were early days for the maturing-internet, where adults assured us teens that all knowledge could still be found at your local library, reminisced about printed copies of spark notes, and discouraged us from researching online because it was, “lazy.”

These were early days for Twitter, LinkedIn, and Google Scholar, aka, where we now find and request niche and pertinent content before we know the right place to look. Reddit and Quora emerged at this time as well, but it was still before the time that a post would receive enough engagement to yield meaningful answers to hyper-niche queries.

All to say, in this temporal-landscape, I knew only about as much as the bookstore clerks, the librarians, and the adults in my life knew. And lucky for me, most of my parent’s friends were architects or psychologists. They must have the answer.

Unfortunately, whether it was because (1) they didn’t seem to see the link, (2) they saw the link but didn’t know where to point me, or, worst of all, (3) never could imagine how serious my query was, for years I was left without the empirical evidence I sought.

That all changed on an after-school walk back home with my mother when we ducked into Bird and Beckett Books & Records in San Francisco’s Glen Park neighborhood. I cannot recall what drove us into the set-back store that particular afternoon, but my mother and I, as always, slid into our respective sections. She found her way to the poetry whilst I did my procedural check through the overflowing redwood shelves: first social science, then psychology, and then architecture. And there it was.

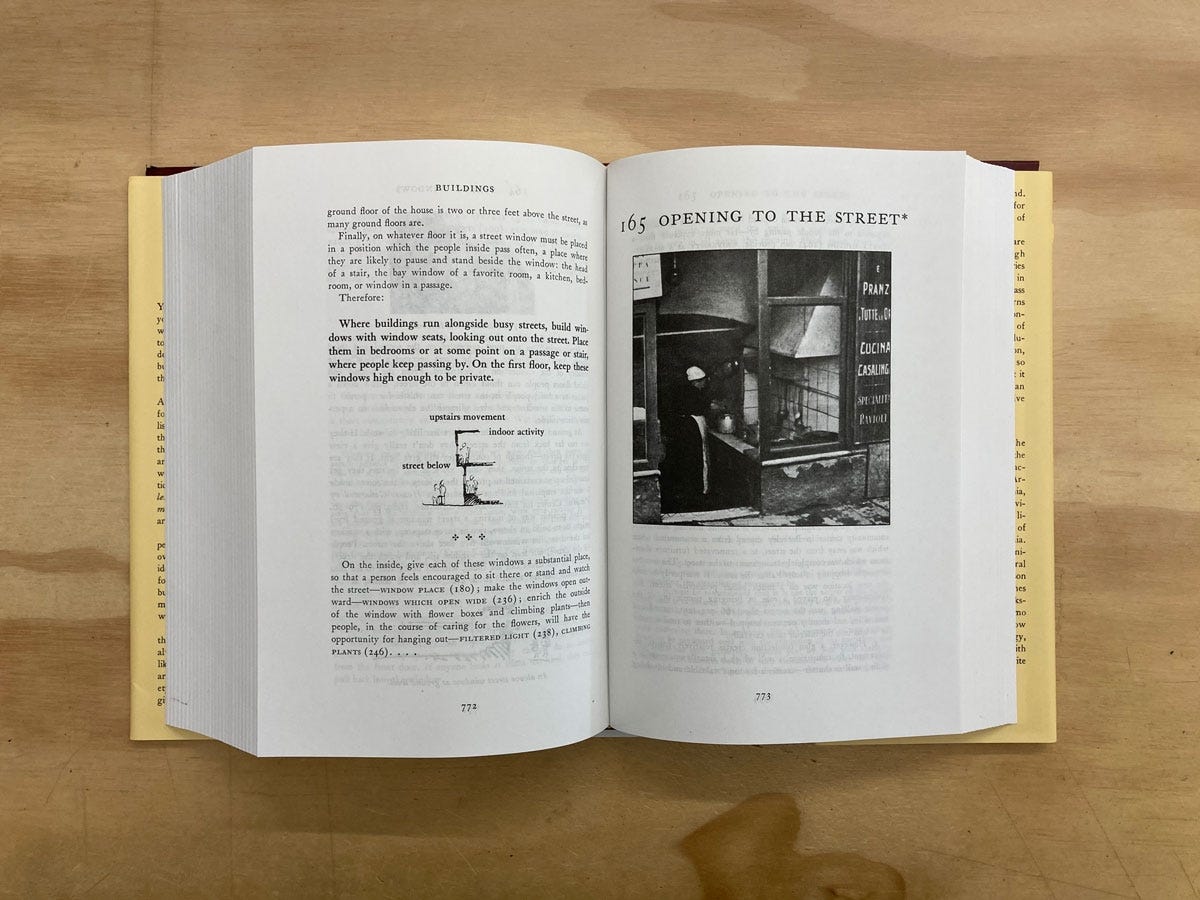

There was nothing about its title that could have tipped me off, there is no knowing what incited me to reach for the bulk and dense of the book with a soft matte yellow book jacket, A Pattern Language (Alexander et al., 1977).

I remember everything about that moment, the sun flowing through the southwest windows, the weight of my orange pop-punk-checked Timbuk2 messenger bag (my desperate attempt at coolness) dragging me down as my restlessness changed to patience (my mother could read as much poetry as she wished by my watch).

It was in that time-warped afternoon that I first scanned the canonical architecture text written by a cohort of UC Berkeley faculty in the 1970s, Christopher Alexander, Murray Silverstein, and Sara Ishikawa. The pages were as thin as a dictionary’s, and for over 1000 pages they juxtaposed social phenomenon with architectural designs with tiny chapters with titles like, “Dancing in the Street,” “Opening to the Street,” “Raised Crossings,” “Corner Grocery,” “Number of Stories,” “Stair Seats.”

Finally. It felt like someone else got it, “there is … work to be done on understanding space and how it is socially constructed and used.”

Eventually, my mother swung by my perch. It was time to go home. “This is what I mean!” I exclaimed in a book-store hush.

But, it wasn’t.

Well not exactly.

The principle of relating built environment conditions to human experiences was spot on. But the “science,” perhaps wasn’t as rigorous as I was truly seeking. (The contents were neither identified methodically nor forthcoming in regards to the regions or demographics to which such conclusions would be relevant … a social science no-no.)

Regardless, I felt closer to something ethereal I had long been after, and was empowered to continue reading, and upon my path fell:

Foucault’s ideas about Heterotopias,

Bachelard’s Poetics of Space,

and, of course, Lefebvre’s work.

These theoreticians emphasized that space is not a neutral backdrop but an active participant in the production of social relations and personal identities. In this way, their works comprise the intellectual inspiration on which my research rests.

From theory, to practice, to research

The transition from personal reflections to broader theoretical inquiries necessitates a bridge: understanding how my lived experiences inform my academic pursuits.

After a youth enamored with buildings and their design, my undergraduate studies in architecture and subsequent work in tech consulting further solidified my interest in the built environment as a dynamic artifact. Or at least with the potential to be.

I came to understand that buildings, and all built things, will become increasingly digitized. The future, for good or bad, will be full of increasing computation. Our buildings will not be exempt from this.

Ready with philosophical theory from Foucault, Bachelard, and Lefvbre, and architectural theory from Alexander, Silverstein, and Ishikawa I wondered how empirical research could inform design knowledge as it related to creating computing-rich environments that enhance human well-being and security.

In short, I pin my hat on the following: there are identifiable patterns between the built environment and human experience. And my ambition as a researcher is to:

Surface identifiable patterns,

understand how design informs the codification of those findings into ubiquitous computing technologies that turn traditional built environments into ambient intelligent environments,

and to ensure such codification is done in a values-aligned way that ensures the security of the inhabitants and property.

It is my aim in my research to understand how design impacts the computationally enriched built environments of the (near future). To that end, and without further ado…

3 Principles for the Future of the Built Environment

__________ 01 BUILDING FOR HUMAN EXPERIENCE

The built environment will be designed to actively support human needs.

We will live in environments that actively support our physical and mental well-being, make our social interactions more gratifying, and increase our productivity.

__________ 02 DATA-DRIVEN DESIGN

The built environment will be design-engineered based on (real-time) data.

Rather than making educated guesses or choices based on gut instinct, our design-engineering behaviors will increasingly rely on data. Everything from the relationship between ceiling height and your cortisol levels to classroom materiality and learning outcomes will be measurable and actionable.

__________ 03 EMBEDDED TECHNOLOGY

The built environment will be able to monitor and react, in real time, to inhabitants.

With the emergence of Spatial Computing(SComp), and the growing interest in the SComp domain of Ambient Intelligence (AmI), we are quickly approaching a time when technology is small enough and smart enough to have a big impact while remaining (relatively) invisible.

Mon Oncle, 1958, Directed by Jacques Tati . Mon Oncle centers around a (spatial) commentary on the emerging wave of industrial modernization in the French consumer society of the 1950s.

Long story long, my bias is that there is a profound impact of space on human experience. And, as our world becomes more digitized, understanding and designing for this impact becomes ever more crucial.

For, as Lefebvre posited, the colonization of everyday life by capitalism extends to our spatial environments, and, as I posit, is made ever more expedited through (uncritical) technological integration.

Recognizing this, working towards *technology-mediated* spaces that support human flourishing, is not only my personal fixation and academic research area but also, a necessary endeavor for a future of the built environment where everyday life is sovereign.

With that, lighter things ahead.